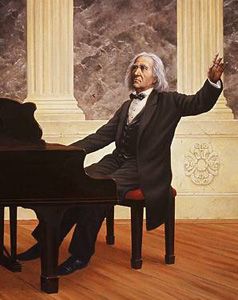

Liszt, Franz (1811 - 1886)

Liszt was the son of a steward in the service of the Esterhzy family, patrons of Haydn. He was born in 1811 at Raiding in Hungary and moved as a child to Vienna, where he took piano lessons from Czerny and composition lessons from Salieri.

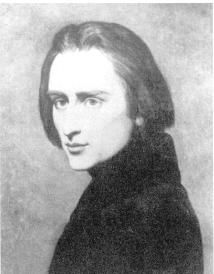

His father, Adam, and grandfather were both land stewards for Prince Nicholas Esterhazy, and young Franz might well have followed in their footsteps had Adam, who once harbored musical aspirations of his own, not recognized his son's amazing precociousness on the piano. When Liszt was only nine years old, Adam arranged a series of public performances for the boy, hoping to interest backers in paying for his musical education. The gambit worked: a consortium of Hungarian noblemen set up a fund that allowed Adam to take young Franz to Vienna in search of teachers. There, Liszt's natural, intuitive approach to the keyboard so astonished the great Czerny, a protege of Beethoven, that Czerny offered to teach the youngster free of charge. The great Beethoven was even cajoled into hearing the boy play and made his admiration apparent. Young Liszt was, it seemed, on a fast track to greatness.

At age 12, Liszt was refused entry into the Paris Conservatoire (on the basis of being a foreigner) and resorted to private tutoring. His public debut in Paris in March of 1824 was a resounding success, and the budding genius was soon playing at all the important salons. But when Adam insisted on further touring, his wife Anna balked and demanded a separation. The breakdown of his parents' marriage hurt Liszt deeply and foreshadowed some of his emotional problems to come. He hit the road with an itinerary - London, Manchester, back to France - that by 1827 drove him to physical exhaustion. Recuperating near Boulogne, Liszt was then shocked to lose Adam to typhoid fever. He was joined by his mother in Paris and became their sole source of support. At the age of 15, he began teaching piano.

Liszt's physical and emotional states were always in a perilous balance. At 16, he fell in love with one of his students. When her father nipped the relationship in the bud, Liszt had a nervous breakdown; so severe were his catatonic seizures that rumors spread that he had died. His recovery was protracted, and he didn't even touch the piano for a year, considering, instead, entering the priesthood.

He was then suddenly roused, as if from a coma, by the street fighting during the July Revolution of 1830 and returned to the keyboard. Liszt's great epiphany occurred on March 9, 1831, when he heard the brilliant violinist Paganini at the Paris Opera House. Liszt vowed to be the Paganini of the piano and began practising as if possessed - up to 14 hours a day. Among his friends and admirers was Chopin, at whose home at age 22 Liszt met Marie d'Agoult, a 28-year old married Countess. In 1835, they scandalized Paris by eloping to Switzerland, settling in Geneva. Liszt and Marie went on to have two daughters and a son, and her wealth provided him with a financial safety net that allowed him to begin composing in earnest, notably a three-part masterwork called Years of Pilgrimage, on which he continued to work in Italy in 1837. But like that of his parents, this marriage also foundered on the shoals of his ambition. Liszt felt compelled to return to the concert stage - first to raise money for Hungarian victims of the 1838 Danube flood, then to underwrite the Beethoven memorial statue in 1839 - while Marie strenuously felt he should stay home and compose.

But Liszt stuck to his guns. For the first time in 18 years he returned to Hungary during the Christmas season of 1839; he visited Budapest and then his birthplace, Raiding, where he chanced to hear the music of the local gypsies and began to write the Hungarian Rhapsodies. (This event is central to the theme of the Devine Entertainment film Liszt's Rhapsody.) Over the next five years, he played to hysterically enthusiastic audiences throughout Europe; thousands would attend his concerts to hear him play from memory for hours at a stretch. But in 1847, he finally gave up the concert stage to devote himself to composition (his marriage was long over), basing himself in Weimar as the prestigious Keppelmeister.

In 1842, touring the Ukraine, he had met Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, a wealthy, separated, somewhat eccentric woman (she smoked cigars) with whom he was to live for 12 years, as he composed the likes of his B minor Piano Sonata and his Dante and Faust symphonies. Thanks to Liszt, Weimar became a musical mecca, the headquarters of the Neo-German School represented by Berlioz, Brahms and Wagner - until bickering and backstabbing by envious rivals poisoned the atmosphere, and he decided to move on.

Although the last 25 years of his life were, as we see in retrospect, surprisingly productive, Liszt suffered a series of tragedies that took an enormous toll. Carolyne became virtually mad in the 1860s, and his son and eldest daughter died within a space of three years. In 1863, Liszt turned, as he almost had as a lovelorn teenager, to the priesthood, entering a Dominican monastery, although he continued to compose on a piano in his cell. In 1867, he "surfaced" to compose the "Hungarian Coronation Mass" for Emperor Franz-Josef. But Liszt knew he needed the peace and security of a safe haven, and for the last 15 years of his life found himself in a pleasant rut: living and working in Budapest from January to March, teaching in Weimer from April to June, and seeking the sanctuary of a villa near Rome for the rest of the year. Thanks largely to this pattern, his last 10 years were gratifyingly creative.

In 1870, Liszt took a serious fall down a flight of stairs and never completely recovered. His eyesight started to go - thanks to cataracts - and money was tight. In the summer of 1886, while attending the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth, he came down with pneumonia and died on the 31st of July. Sadly, the burial of this tormented genius was all but obscured by the gaiety of the crowds who had come to honor Wagner.